Book Review: “Tunnel to Hell: The Lake Erie Tunnel Disasters – Tales of Heroism and Tragedy” by Scott MacGregor

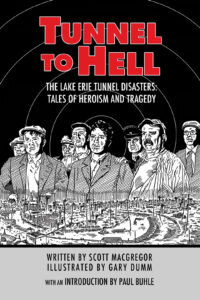

Tunnel to Hell: The Lake Erie Tunnel Disasters – Tales of Heroism and Tragedy

Author: Scott MacGregor

Illustrator: Gary Dumm

ISBN:1619847809

$19.99

Love and Labor in America

Review by Beth Osborne

In recent years, the graphic novel genre has begun to pull away from fantastical, Lycra-clad heroes, highlighting instead the unsung and extraordinarily ordinary. Enter Scott MacGregor’s Tunnel to Hell, a gritty tale exploring the blue-collar experience in 1916 Cleveland.

The story opens in Atlanta, Georgia, at the July 1916 American Fire Chief’s Convention. Ben steps out on a stage dressed as a Native American, despite actually being black. Ben quickly illustrates to the reader that it is better to have “Native” rather than “African” attached to your American. Once his disguise is found out, a brawl ensues, and in it MacGregor reveals that anyone viewed as Other – be you black and/or Irish and/or Catholic – isn’t safe.

This concept of safety, and its lack, permeates MacGregor’s entire narrative, as it follows Ben and Clarke through their struggle in race, religion, and class in early twentieth century Ohio. As we hurtle toward the story’s climax of the Waterworks Tunnel Disaster, we learn of the uniquely precarious environments each character is attempting to survive. Sharing top billing in the story with Ben is the character Clarke, an Irish immigrant who makes his living working in the tunnels. When we first meet him we know that he has injured his leg, and later learn that this injury came from a previous incident in the tunnels. An omen, it seems, for what’s to come.

MacGregor uses the juxtaposition of characters Ben and Clarke to provide for his readers an excellent societal backdrop for the times. Ben struggles to be heard and prove his worth in a time of violent racism where, as one character puts it, no one will “accept a negro as the hero.” By contrast, Clarke struggles in lower middle class, where his life and the lives of his peers are viewed as expendable by the rich and the powerful making decisions. As shaky infrastructure buckles underneath the pace of progress, the reader wonders if anyone will make it out of this story alive.

What is most shocking about MacGregor’s story is not the grim reality of how the Waterworks Tunnel Disaster of 1916 unfolded, but how the themes echo through a century and resonate today. These questions of race, of the wage gap, of the risks that our failure to tend to our infrastructure create, are questions that we still ask in earnest today. This story is not important simply because it is interesting and should be heard, but because a similar story could be told today; simply substitute the Irish Catholic immigrant narrative with any of the anti-immigrant sentiments that one needs only to turn on their television to hear.

The art of this graphic novel successfully captures the stark nature of the lives MacGregor fleshes out. Illustrator Gary Dumm uses simplicity in his panels to add another layer to the story. His illustrations are direct and without frills because the characters live simply, in poverty, in oppression. At times the panels feel crowded and bleed from one to another, providing for the reader the physical experience of being pushed out or being left behind, which are experiences the characters must work through every single day. In Tunnel to Hell, the illustrations inform the narrative, providing in pictures the nonverbal struggles each character must face.

As a disembodied narrator tells us at the close of the story:

“History lives at the pleasure of a forgetful human race. More often than not, the extraordinary achievements of simple ordinary men and women evade history altogether or barely survive within the decay of tattered memories.”

Despite the social, economic, and political strides one generation can make, it seems as though the generation to follow picks up at the starting line. No clearer is that made than in MacGregor’s choice to close his story with a surviving character speaking with his grandson. “Old people like me,” the character says, “We’re outa time and leavin’ behind a big job for the next generation to finish.” While it’s a hopeful note, it is important that the character shares this with a grandchild rather than with the preceding generation. Not only is it too late for “old people” like him, it is also too late for the parents, undoubtedly in their thirties or forties, who have also failed to move past the dangers and the prejudices of years past.

So many tragedies in history are left untold or relegated to footnotes in the wider narrative of history. MacGregor takes the story of twenty senseless deaths and funnels them through the lenses of classicism, racism, and the unrelenting pace of progress, which not only sheds light on the lives and deaths of these men, but calls our attention to how progress still treads on humankind, and how close we still stand to the mistakes of yesterday.

Beth Osborne is a chocolate enthusiast living in Ithaca, New York. When she isn’t reading books, Beth can be found wandering in the mountains, baking bread, and training for triathlons. Before she was reading, Beth was a paleobotanist. However, a harrowing experience at a Costa Rican theme park convinced her to pursue a quieter life.